Frogs and PIT tags… must be fall! Part 2

Posted onOctober 28, 2025byJenna Kissel|Fraser Valley Wetlands, Fraser Valley Wetlands Wildlife, News and Events, Oregon Spotted FrogPhoto: J. Kissel.

What is the Oregon Spotted Frog Recovery Program? Since 2010, WPC has been breeding the endangered Oregon spotted frog at the Greater Vancouver Zoo, and reintroducing thousands of tadpoles and froglets back into wetlands in B.C.’s Fraser Valley. It takes years of careful observation, collaboration, ingenuity and sometimes a little luck to crack the code to breeding specific species. For several years, our progress was very limited. But our team persevered. Today, WPC has pioneered breeding techniques that are turning the tide for this species.

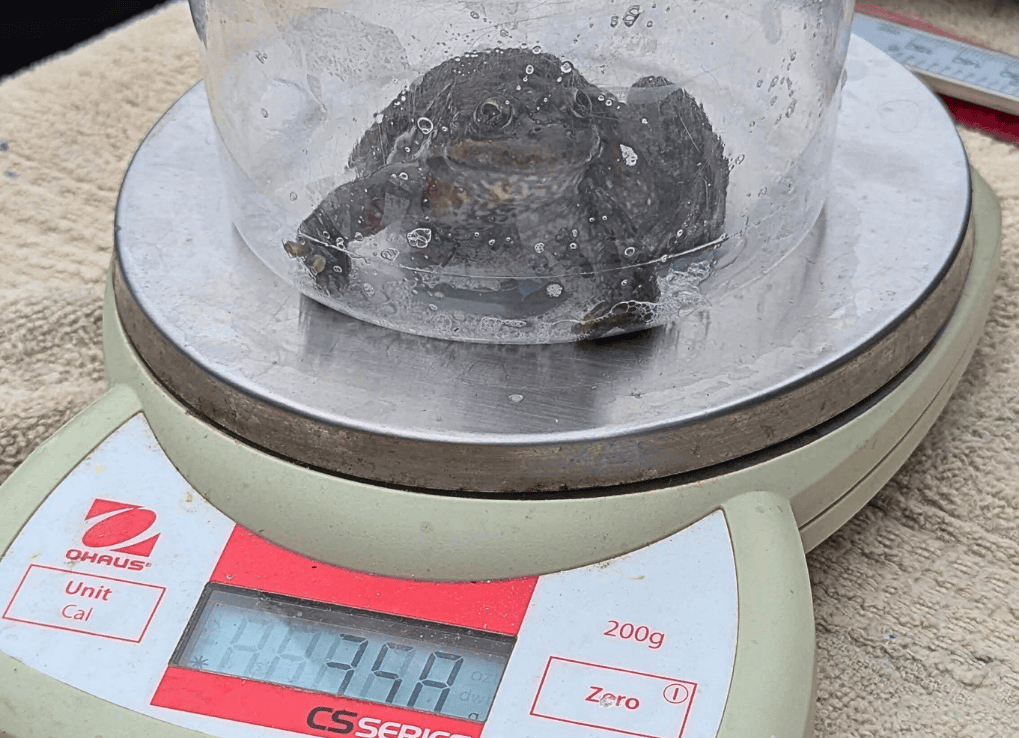

Frog marking day is one of the last chaotic days for our team before things start slowing down for the winter. Most of the day is spent preparing the year’s froglets for release – but the froglets aren’t the only ones that get processed on frog marking day (read about our froglets in Frogs and PIT tags…must be fall! Part 1). We also process the adult Oregon spotted frogs and get them ready for winter. All the adult frogs are collected from their tubs and identified using their PIT tag number. We take the same measurements as the froglets – we measure their snout to vent length, shank length (the leg length between the knee and ankle), and weigh them.

After they’re processed, the males and females are separated into their own tubs for their winter hibernation. We can identify the males from the females because the males have a black pad on their thumb called a “nuptial pad” which helps them hold onto the females during mating. Over the years of trials and tribulations, we discovered that keeping the males separate from the females over the winter creates the “magic” water in the female tub that has led to our egg-laying success. The males and females stay separate until February-March, when we wait for cues from the field team that wild male Oregon spotted frogs are starting to move and court females. That’s when we reintroduce the males in our program to the females for breeding in their love tubs.

As the weather cools, the frogs prepare for their long winter’s nap. To avoid freezing, the frogs hibernate underwater by partially burying themselves in the vegetation or silty soil of wetlands that are deep enough remain unfrozen at the bottom. They don’t completely bury themselves because they need access to oxygen – frogs breathe underwater by absorbing oxygen through their skin. During hibernation they lower their metabolic needs, so they require very little energy and less oxygen than usual. The frogs in our breeding program located at the Greater Vancouver Zoo remain outside in the large tubs they live in during the warmer months, with a few modifications. The outside of the tubs are wrapped with heated cables and insulation to keep the water inside from freezing solid.

Now that the frogs are tucked away for the winter, they are pretty low maintenance. We’ll keep an eye on them to make sure they are hibernating comfortably and to prevent ice from forming too thickly on the water’s surface, especially during freezing temperatures and snowstorms. Thankfully we don’t have to worry about that too often in the Lower Mainland!

We need your help