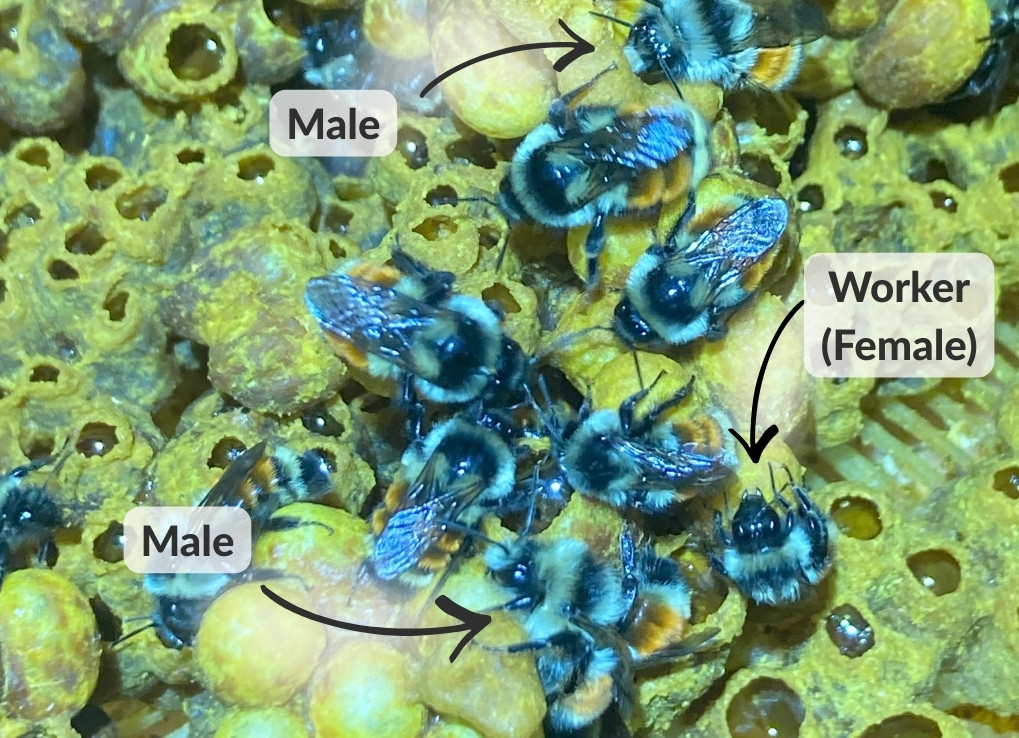

Just like workers, males will wrap their legs around pupae and pump their abdomens to generate heat. Maintaining the temperature of the brood is a key to-do in the colony, as letting it drop too low will result in longer development times, pushing back the emergence of males and gynes who already have a short window of opportunity to leave the colony and find mates before the weather starts to get colder. While males aren’t as good at increasing the temperature as their female counterparts, their ability to maintain the temperature of the brood after workers or the queen have raised it up to a good level is crucial in keeping up with colony development.

So What?

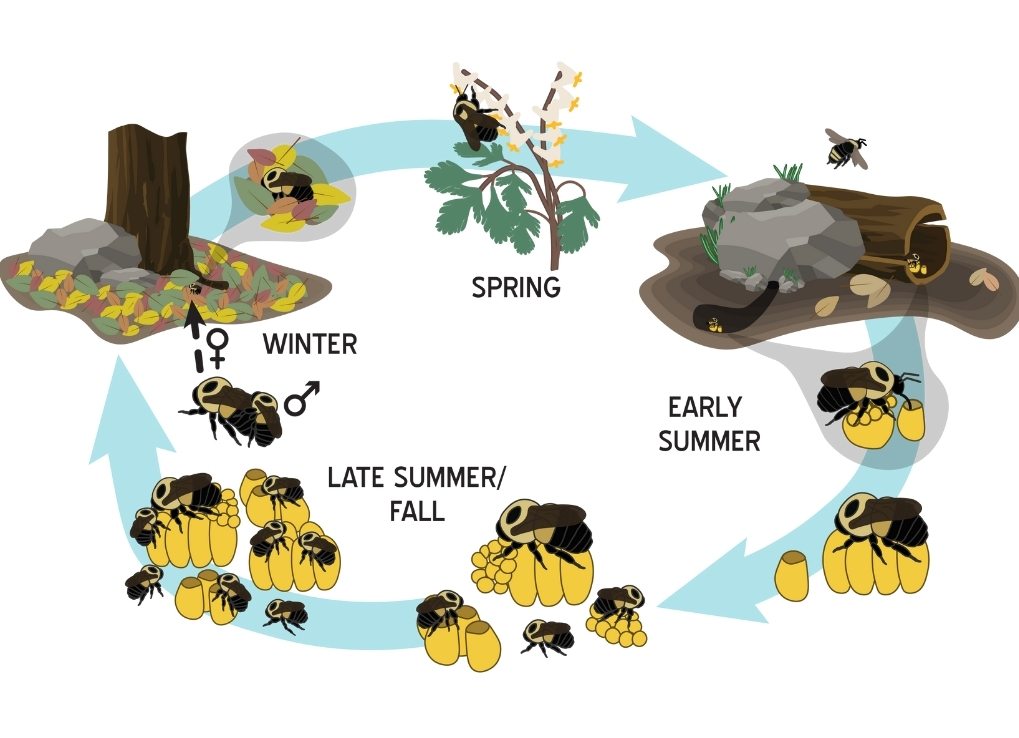

Partially I just want everyone to know about this because male bees get a bad rap, especially considering how cute they are. But also, with all of the focus on queens and gynes (who are the most visible when you’re out and about, and are what we usually pay attention to here in the lab as a success metric) and workers (who are the powerhouse of the cell colony), it can be easy to forget about the “lowly” males. Conservation must consider the whole lifecycle, and with it, all parts of the colony – male health and abundance affect population health and recovery, too!

So the next time you see a male bumble bee (most species have a yellow patch of fuzz on their faces, but you can find a full description of their differences on the backs of our ID cards), thank the little guy for his service!

Learn more about the bumble bee life cycle here, and follow/share to help challenge common misconceptions!

If you want to dig in and read more about the importance of males to bumble bee colonies, check out this article by Belsky, Camp & Lehmann, and it’s references.